Long entangled in a bizarre ownership structure that split the structure’s ownership between a private company that held the building’s lease and City of York Council and North Yorkshire County Council that shared the freehold, the fate of York’s Stonebow House has finally been sealed.

For decades decried by many in the city as an eyesore, not in keeping with York’s “historic aesthetic” and self-image, Stonebow House’s brutalist structure is in the words of one critic “one of the few proofs [in the walled city at least] that the 20th Century happened in York”. For years from the York Press’ letters page and message boards to the conversations overheard in the pubs, there has been a clamour in the city for Stonebow House to be demolished.

Now it will not be. The building and the land upon which it sits have been bought by the Wetherby based Oakgate Group who propose to comprehensively refurbish the building. Their plans, which obliterate the building’s exposed raw concrete, whilst keeping its essential form intact are doubtless not entirely to everyone’s taste. However, in the main it in principle a sensitive, low key revamp that avoids the waste of demolition and retains a key York landmark from an important period in the city’s history.

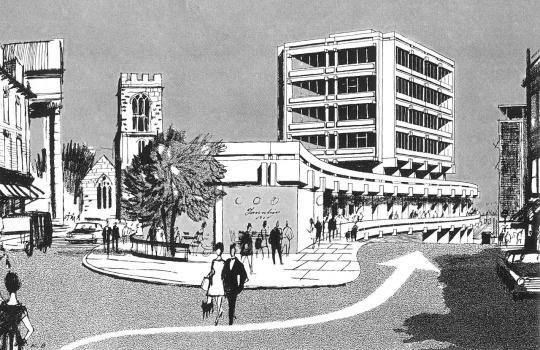

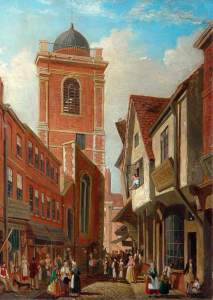

Opened in 1964, Stonebow House was intended as a key component of the York Corporation’s long running (and still arguably incomplete) plan to comprehensively redevelop the poor quality buildings and environment in the city’s Hungate and Walmgate areas. Always poor quality, marshy land (which as Christmas’ events prove remain at the mercy of the River Foss) the area’s awful slum housing had largely vanished in favour of industrial units by the time that Stonebow House was built.

Constructed alongside the newly created Stonebow road, built to open up the city’s Hungate and Aldwark areas for redevelopment, Stonebow House-it was hoped-would act as a beacon for a newly prosperous York.

As it happened the turn to conservation, a species of postmodernism which first emerged in the later 1960s, rendered the building’s brute scale and unabashed modernity passe, even crass, within a few years of it being finished and let. Out of favour, even as far more monumentally imposing structures like the Coppergate Centre, York Barbican and the North Street Office block now inhabited by AVIVA, all of which genuflect somewhat towards the vernacular idiom, were constructed, Stonebow House took on a less flashy role in York’s civic life. In recent year it has, quite fittingly, become something of a haven for the odds, ends and misfits of York.

Providing a home to Fibbers (which moved out in the summer of 2014) and to the Duchess, for over 20 years Stonebow House was the residence of the two venues that showcased York’s more interesting homegrown musical talent and visiting bands that would have had nowhere else to play. Two generations of indie kids, punks, goths and ravers wouldn’t have had any other venues in their somewhat geographically isolated hometown. Likewise the existence of Fibbers and The Duchess meant students at York Uni and St. John’s got a bit of a taste of the more varied and exotic music scenes elsewhere.

In a less rarefied and all to concrete way (pun fully intended) the shops and services housed in Stonebow House (the Jobcentre, Heron Foods, and York’s local independent bus company) provide vital services to the city’s poorest and most marginalised residents. Services which would otherwise struggle to find a home in the centre of one of Britain’s most expensive (but not especially high wage) cities. York’s gentrified city centre, dependent as it is on pubs, coffee shops, restaurants and boutiques is not a welcoming place for a person without personal transport. As in Paris most of the city’s bourgeoisie shop in the retail parks, dotted around the outer ring-road, miles out from the city centre, but easily accessible to North Yorkshire’s gentry, from which the city’s poorer and more marginalised residents are spatially segregated.

Considered aesthetically: the building’s exposed concrete hasn’t weathered the wind swept and bitingly cold east Yorkshire climate all that well. Likewise, there is little pretty, twee, or overtly “historic” about Stonebow House’s hard, angular form. But the same can, and has been said, about the structure and form of John Vanbrugh’s Castle Howard, and York’s worthies named a college at their university after him.

Arguably the worst place to view the building from is from the place that most people first glimpse it. The junction, at Whip-ma-Whop-ma-Gate where Pavement becomes Stonebow. Viewed from up close, or from the structure itself, the shear swirling intricacy of the building, its geometric virtues, are abundantly apparent. The concrete staircases, striking and unusual in the way that they slot together, very different from most other British brutalist structures, recalling French, Italian or Latin American buildings of the period are especially worth seeing.

Stonebow House is also worth viewing from afar. Glimpsed from the city’s walls over on the far bank of the Ouse, just down from Micklegate Bar, its tower-soon to be converted into “luxury apartments”; looks just like a slightly squatter version of all the other steeples spread out across the city. The tower in fact has a very sympathetic relationship to the church towers that it stands in relationship to. Taken in from the side, or from the deck like car park, atop the first floor, the viewer is left with the impression that the building complements the church towers around it, especially the mighty lantern of All Saints, Pavement.

At the very least a viewer of this felicitous and deeply complementary arrangement comes across feeling that the architects of the mid-20th Century had a far more sensitive relationship with the past than they are often credited with. At the most, a more superstitious visitor might be inclined to see in the form of Stonebow House the ghostly vestige of St. Crux Pavement, an unusual 17th Century church building demolished in 1887, because its baroque styling did not meet Victorian notions of piety and decency.

The pictures below were taken by me in January 2014, whilst I was working for a magazine in York, for an article about Stonebow House that wasn’t eventually published.

If you’d like to see inside the currently deserted office block then The Press has a good gallery.